With all this talk recently about artifiicial intelligence, we need to be careful with its application. A fairly long time ago I was Chief Geologist for a mining company that had recently purchased an operating gold mine on a southern continent, the geological staff of which was not able to correctly forecast the monthly production from its sampling. In the role of mentor and troubleshooter, and also to be a company leader for upholding high standards and fostering technological innovations, this mine, shall we call it “Golden Mafia”, was my focus for a couple of years. The problem was that the mill was receiving more tons and lower grade than the mine geologists reported sending on monthly, quarterly and yearly bases. This, of course, is a very rare phenomenon in underground mining where extreme care is taken with sampling and reporting by highly skilled and compensated mine geologists and technicians. Sampling and sampling technology is always the #1 priority for the management team, right? Historically, these types of variances, when they occur, are invariably attributable, according to reliable geologists interviewed for this article, to inside criminal elements skimming gold in the mill, to production engineers’ and metallurgists’ “adjustments” and to the 10% tithe to the “Big Guy”. But there was something curious about the Golden Mafia, not explained by the usual factors, or the cronyism of the expat management group that came from yet another country on the same continent. It bore further research.

I worked with the team at the mine, and together we formed the “Find the Missing Gold Task Force”. I shadowed the mine geologists on their daily beats (by the way, the term “Beat Geologist”: Shouldn’t it be banished from the mining lexicon? It is racist.). In the office, we huddled around IBM XT super desktop computers to transfer the raw data to new and modern digital formats, availing ourselves of the collective decades of mining experience assembled in the overly air-conditioned mine office to solve the problem. We ignored daily distractions such as the betting pool on the cafeteria main course (brussel sprouts again?), invasions of leafcutter ants destroying a tree in the adjacent patio outside, arguments about how to distinguish the poisonous snakes from the harmless ones, pictures of a guy getting eaten by an Anaconda, and the latest news about invasions of illegal miners on the neighboring concessions. All remaining attention was focused on how to reconcile the mine and the mill.

This was the 1990’s, the Golden Age of technological innovation. Anaconda the company was history, RC drilling was king, and flow-through shares was still gasoline on the fire. Harry Parker was just now publishing his chef d’oeuvre on reconcilation between mine and mill. Al Gore had just invented the internet, but there were still isolated pockets not connected by Gargle, where parallel evolution was possible and was indeed happening. Golden Mafia was one of those places. Our research into variances between mine and mill spanned several northern hemisphere seasons, fractures in the ozone layer, floods in Caracas, earthquakes in Chile and coups in various countries, but we soldiered on, riveted to the problem, committed body and soul to the solution. Drill and blast, drill and blast…

A breakthrough occurred with a tool, the spreadsheet, which had only emerged a decade or so earlier, but was finding greater and greater utility for making disparate figures and tallies reconcile. Reconciliation, this marvelous 14-letter word that simply rolls off of the tongue, something like “artificial intelligence”, but less oxymoronic. In Spanish it means lovers getting back together. In a spreadsheet, it means getting numbers to match. After months of arduous research, rest breaks taken in very agreeable locales with family, long layovers in airports, extremely dangerous transits of the Pan American highway, demonstrations and road blockades, CIA-sponsored uprisings, fishing expeditions tacked onto company-paid business trips, and exhaustive literature searches covering the extensive university studies on grade control, we discovered the magic offered by EXCEL, a program heavily plagiarized from Lotus 123 by an entrepreneur in Seattle with absolutely no intelligence agency support whatsoever. We found that if we applied a factor generated by a mathematical model in a cell-wise fashion to the mine sampling figures for a period, we could make them approximately equal to the mill totals. The degree of equalness was generally dependent on the number of significant digits, but if any variance remained it could be adjusted by application of a rounding factor. Another conciliaciόn, as it were…

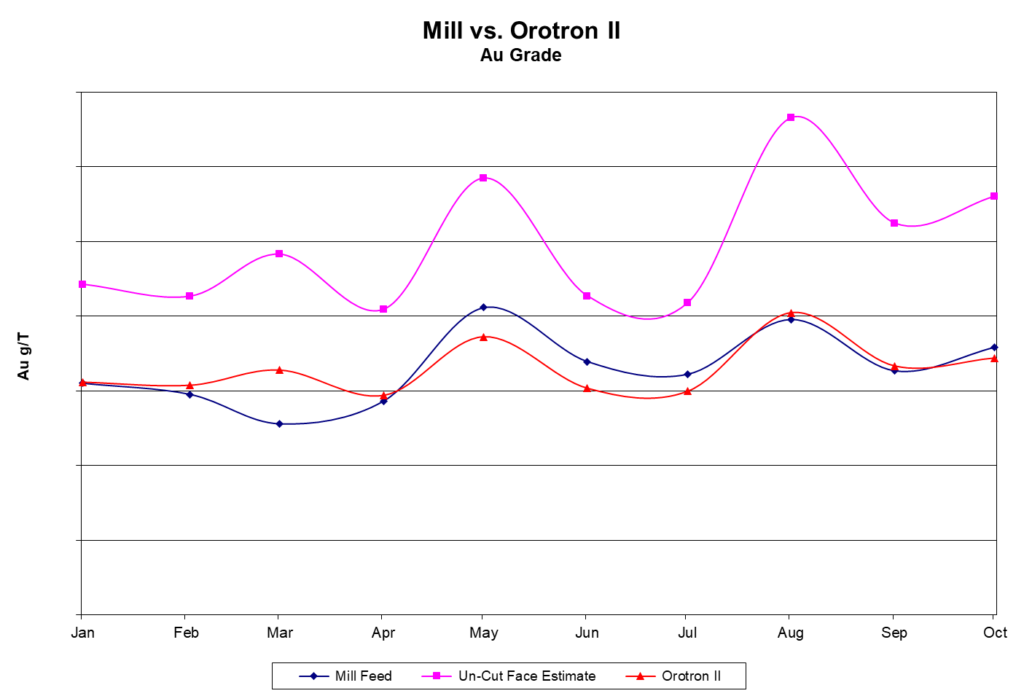

The results were nothing short of spectacular. For the test production periods tested, the prototype algorithm produced mill/mine variances between 0% and 5%. The spreadsheet with the embedded mathematical model (formula) was saved and given the name, appropriate to the significance of the discovery, Orotron.

But, my company was a highly respected name with a legacy dating back several centuries and a reputation for conservatism and high standards of practice oriented to profitability and return to shareholders. It had espoused best practices throughout its recent history, saved capital and operating cost, created directors of Technical Services to keep geologists under wraps, and controlled expenses for boring stuff like sampling and drilling. Given the tradition of the company, we had to vet any new technology with scrutiny by senior staff and outside consultants. We rang up Dr. Harry Parker himself for advice but his phone was busy. Nevertheless, availing ourselves of the comments and criticisms of our broadly experienced in-house resources, we modified the Orotron. The final tool based on Phase 3 testing and peer review was Orotron II. During subsequent field testing and application in the ensuing years Orotron II had a success rate of nearly 100%, safe and effective.

We were able to at least replicate, and often exceed, reconciliation factors espoused by the method of Dr. Harry Parker in the ensuing quarters. It was a great example of parallel evolution, although I willingly concede that Dr. Parker’s methods will stand the test of time and are a little more comprehensible to technical staff.

Innovators and early adopters are often casualties in the continual evolution of technology. In my personal situation, and, Dear Reader, this part is no bull, we actually did call our little baby Orotron II. I think word got out to the company CEO, not a geologist. He heard about this cool technological innovation catching the company on fire, and how it was helping forecasting at Golden Mafia. Things were great there at the mine. We were mining two ore shoots that could have supported Hunter Biden’s coke habit and still made a profit, and it was saving the company. That is to say, we were trying to predict if the mill monthly head gold grade would be 40 g/T or 30 g/T, either way a winner. One day I was walking the halls of headquarters, probably basking in my technological prowess, maybe planning my move to Palo Alto to establish a consulting firm that would surpass Parker’s MRDI, when the CEO bumped into me and casually asked me with a most friendly approach: “Say, tell me about this Orotron II…” In a moment of unguarded honesty I told him: “Oh sure, well actually it’s just a formula in EXCEL”. I knew right then-and-there from the look on his face that we had a problem. Since, besides my technical expertise, I am very good at reading faces, I imagined his thoughts: “This is my Chief Geologist and this is the ‘technology’ I just bragged about to the Board of Directors, a formula in a blinking spreadsheet.” At that moment I suspected that this encounter was not going to lead to my hoped-for February mega-bonus linked to outstanding performance. Subsequent non-encounters with the CEO seemed to confirm this. Also, since Orotron II was such a success in predicting the mill grade from the mine samples, there was just nowhere to go in the company, no more research opportunities, my job there was done. Thus, I was most gratified to receive a very good offer to help build a much bigger mine in a former Soviet republic that gave me a gracious exit, and where research could be pursued without the strictures of the Western scientific establishment. And, frankly I was glad to leave anyway. As an old colleague of mine from my Anaconda days was fond of saying: “___ ‘em if they can’t take a joke.”

Nevertheless, I am considering a roll-out of Oroton III, same features but on a mobile platform so that you can consult it on the go. Anyone interested, please contact me or donate to my Orotron III when you check out with the Cart. Use Promo code OROTRON to ensure a generous matching contribution from the people of Ukraine — otherwise please be kind. This post is based on, and adapted from, events that really did occur, mostly, or at least to some degree. Well, you decide.

Postscript: In the ensuing decades of discussion on the topic of reconciliation, and thousands of man-hours of on-the-ground experience since the 1990’s by many workers in the field, the fundamental concept of the Orotron has been validated . We know now why the Orotron is such a powerful tool and produces reconciliations between mine and mill of nearly 100%, almost always.

Mines are built and staffed in a period of months. The Technical Services Manager, usually an engineer by background, but in some of the most unfortunate cases, a geologist, generally decides to use the grade control method from the last mine where he was employed as a template for the new mine. The General Manager then applies his automatic 20% budget cut for grade control to that bare bones program to make the Year 1 operating numbers look good and help pay for the overruns in the mill and G&A costs. After all, we all need to get paid and he didn’t produce this show in the first place. This leaves geology with a few bundles of sample bags, one technician and an on-off drilling program. Once this system is in place, no matter what happens in the mine or to prices, or to personnel changes, the system is engrained in the culture. The reconciliation between the sparse, inadequate and biased samples and the mill is never “good”. You can spend a lot of money, time, resources to find out why—it’s almost always the same set of problems—or you can apply the Orotron. The benefit of the Orotron is high morale and less distractions for the technical staff, thus, higher safety performance. There are no more inquisitions to discover the lost ounces and the culprits involved. The focus of the team can return to reducing operating costs, including grade control, which, if deemed high, can revert to the 50¢ per ton which it should be anyway, right? And how do you tell the poisonous snakes from the harmless snakes, anyway?

Test